I had it backwards back in Pittsburgh...

Reflections on the G20 in Pittsburgh in 2009... my first time getting tear-gassed

A van pulled up alongside me, headed the wrong way down a one-way street. The door slid open. Men in riot gear spilled out, a dozen of them, with something like glee on their faces. One man stopped. He took stock of the frightened students who’d paused to watch all the chaos. He nudged his buddy and bellowed, “Time to kick some ass!” He slammed the visor down on his helmet, and he went running into the crowd of students, his baton swinging.

Moments later, I would swallow a mouthful of teargas in the lobby of my freshman dorm.

Huddled in the lobby, confused, coughing, afraid, trying to take video, trying to take pictures, trying to figure out what was going on, I’d listen as a gruff man in body armor threatened expulsion for anyone who didn’t enter their dorm room immediately. He shouted over the crowd, “It’s like if the government declared martial law, okay? But they haven’t.”

Pittsburgh, 2009.

I was 19.

That September, Pittsburgh hosted the G20 — a meeting of twenty of the most powerful leaders in the world.

The Obamas had breakfast at the pancake spot we all loved on campus. It was exciting. Protesters from all over the world had congregated in Pittsburgh, too, holding marches anyway even though their permits had been denied.

The cops — dozens of agencies from around the country, all assembled in Pittsburgh like the leaders and the protesters — cracked down, hard. They blasted us with an LRAD — a Long-Range Acoustic Device. It’s a military-grade “sound cannon” that can cause permanent hearing loss, hitting us with piercing, shrill, ululating sounds that caused instant headaches and made people instinctively turn and run.

It was the first time such devices had ever been used on American citizens.

And each night that weekend, on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh — which is really just the neighborhood of Oakland; it’s a campus in a city, where life continues around academia — hundreds of riot cops terrorized students who were just out for an evening walk. On their way to house parties, or heading back home from night classes, or to meet up with friends for some grub at the dining hall, or simply looking to see what all the commotion was about, kids were beaten, arrested, tear-gassed, trampled by horses. Shot in the face with rubber bullets. Incessant helicopters thumped overhead, shining spotlights all over the streets, sending students dashing for cover.

And the national media... just didn’t care.

Social media was new.

I was on twitter already, and I sent out dozens of frantic tweets hashtagged #g20pgh, begging people to pay attention to what was happening to us. I posted about it on Reddit. I uploaded my videos to something called iReport, which I think was a CNN project soliciting citizen journalism? iReport doesn’t exist anymore, and I would later delete all of those tweets, paranoid they were about to be used against me.

I was writing for an alternative online student news source that year, and my friend Josh and I were out in the streets trying to report, to document, to take photos of what felt like it should’ve been the biggest story in the country.

I was the writer; he was my right-hand photographer. He’s great, and he taught me so much about taking pictures. We’re still best friends today.

At some point — around when I got tear-gassed in the dorm lobby — we got separated. Josh took a video of a student being shot in the face, and he helped the guy jump over a wall into an alley, and they hunkered down for safety in the hot dog shop around the corner that was known for serving massive piles of french fries that really hit the spot when you were drunk. On his journey back around the block to the dorm — as I was told we were under martial law, except not — he would take video of a group of laughing cops posing for photos with a handcuffed student they’d arrested, forcing him to his knees in the middle of the street.

Later, sitting on the floor of Josh’s dorm room, I recorded an interview for a podcast over Skype.

I begged them to alter my voice, because I’d heard of students threatened with expulsion for going public with the story. Trying recently to reconstruct those frantic days that followed by digging 16+ years back in my gmail, I think I learned that I might’ve been on a podcast put out by Breitbart. Yikes.

I was 19. I largely had no idea who I was or what I believed; I was just desperate to be heard, and they emailed me.

I’d quite literally run into John Oliver — then a correspondent for The Daily Show — at one of the marches. I knew he must have known what had happened to us; surely he and Jon Stewart would break the story wide open!

We all eagerly awaited his segment on the next episode of the show... only to find that he’d turned in a segment about a guy in a cow costume and how it seemed like “the protesters didn’t have any coherent demands.”

It was a preview of how the Occupy movement would be undermined a year later, denying the reality of the situation to make it all seem like the foolish whims of bored people lashing out... rather than the militarized overreaction now looking like an early warning sign of full-blown, blossoming fascism.

I’d been the editor of my high school paper, and I’d written for my local county weekly, and I’d thought about going into journalism. But this was too much for me. That year, dealing with what I now think was likely undiagnosed PTSD — waking up sweating any time a helicopter flew past my dorm in the night, my vision fading when I saw scorch marks (which lasted all year) on the sidewalks, markers of where tear gas canisters had detonated — I fell out of love with it all.

It was impossible to get anyone to pay attention to us, and it frightened me how completely the story seemed to have been locked down on a national level. What could I do about that?

I slipped into deep denial.

A friend and I dressed as “an unlawful assembly” that Halloween, trying to find humor in what we’d been through.

A few months later,

I wrote an exposé of a “Freedom School” event meant to take place on campus. An outside group who’d been involved in the G20 protests had reserved campus space to hold teach-ins for students on “education disruption” as a tool of protest, promising a “trial by fire.” We’ve been disrupted enough, I thought, buying in fully to the “outside agitators” lie that’s worked a million times in the years since.

After my article went up, I got a call from the Dean of Students within the hour. The approval for the event was revoked. I got death threats and was accused of not caring about freedom of speech, of being a fascist who wanted to limit the free expression of my fellow students.

I shouldn’t have written that piece; I’ve regretted it for years. I’m glad the site didn’t outlast our time in school.

Because we should’ve “disrupted.” We should’ve refused to go along with anything, because the school had clearly gone along with whoever was in charge that weekend on campus. They’d sold us out, had let us be arrested and beaten in the streets, and instead of leaning in to how betrayed that made me feel, I ignored it and ran the other direction, back into the safety and security of denial.

I’d later work for that university for seven years after graduating, and my office was in the same dorm lobby where I’d been tear-gassed.

Eventually, the memories faded.

I recently asked Josh to send me his photos and videos from back then.

He’d asked me if our experience at the G20 lit a spark that’s grown into what I’ve been doing this year in Los Angeles. I said that I thought it probably had, that I had a sense I was making up for lost time.

He quickly had a Google Drive link ready for me.

It’s wild to watch this video now, to see myself at 19 photographing lines of riot cops sweeping through a dormitory quad. I look awkward and gangly, wearing the most hideously-proportioned outfit you’ve ever seen. Why do my shorts nearly reach my ankle? Was I really walking backwards in flip-flops while reporting on a protest? Who did I think I was?

…I was someone who’d just come out to his parents a few weeks earlier, and it had gone horribly. (They’re better now, and so am I!)

Which is to say… I was not in a good headspace that year.

Looking back through my gmail archive, I found borderline-hysterical emails recapping everything. I’d sent them to my grandfather, and the AP Government teacher I’d hated a few years earlier, and the Peace Studies teacher I loved who would invite me back that Christmas break to tell his students what had happened.

It’s funny to see my old photos now, through the lens of the protest photos I’ve taken in 2025. There are so many through-lines, so many things I didn’t remember being interested in back then, things that feel new and interesting now in ways I haven’t let myself feel in a long time.

I still love finding things in an environment that comment on the action.

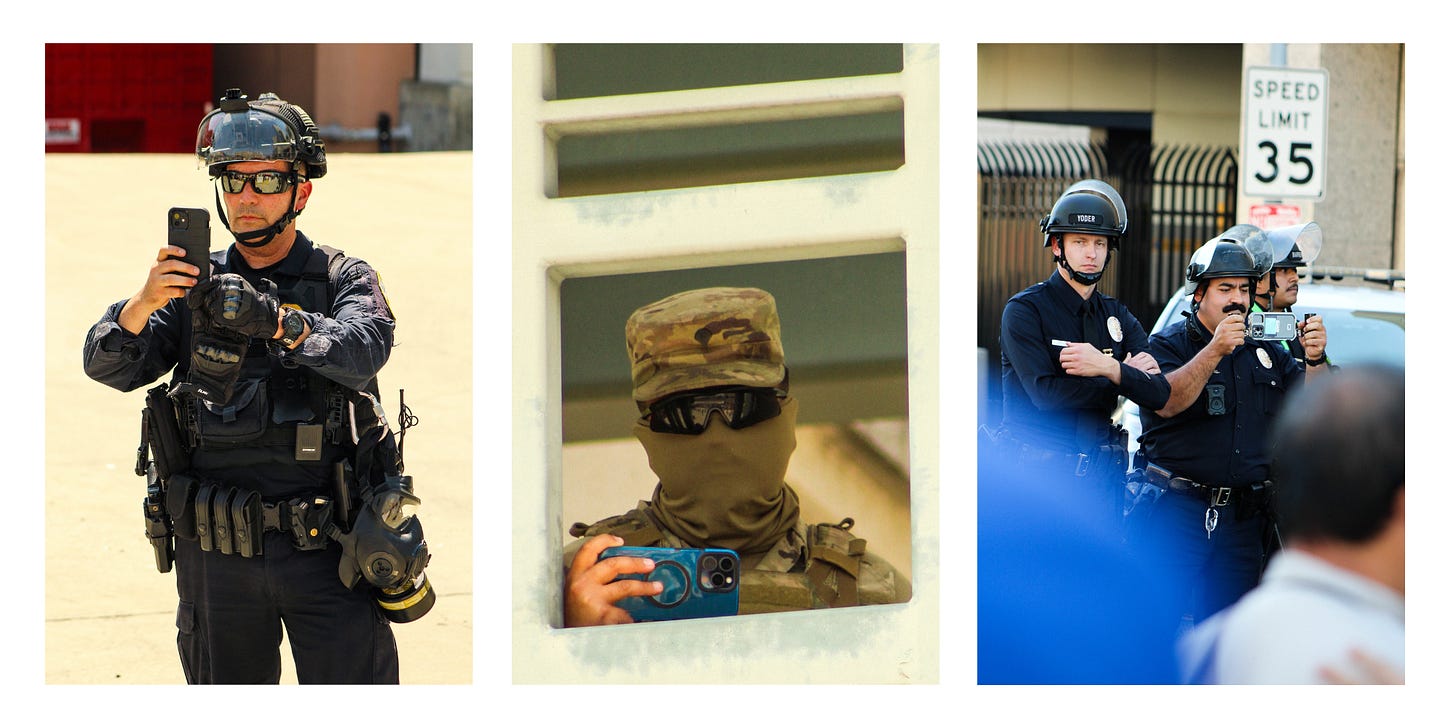

The other day, I shared a bunch of photos like these on Instagram, reflecting on a theme I’d noticed in my own work from throughout the year.

Today I found this one I didn’t remember taking back in Pittsburgh in 2009.

Of course, I was probably just copying my much-more-talented friend. Here’s one from Josh’s Google Drive folder:

The more things change… you know the rest.

I feel like I’m no longer running from the responsibility of bearing witness, no longer worried about who I’ll anger by trying to document what’s happening here.

Back then, I was deeply unsettled by the way those men in their riot gear went swinging at students, filling my campus with hulking silhouettes meant to frighten me back into my dormitory.

Now, in LA — faced with new incomprehensibly-inscrutable forces trying to scare everyone into silence — I find myself trying to photograph their faces, their emotions, to understand what exactly moves someone to sign up for a life of doing that to their fellow human beings.

At Pitt after the G20 in 2009, I was life-alteringly upset by the fact that my reporting and my friend’s photographs didn’t lead to accountability for people who had clearly relished their chance to brutalize students.

Now, in Los Angeles in 2025, I understand that change is hard and it takes a very long time. I’m not taking photographs (just) as a warning for now; I hope I’m documenting things so that, someday, someone can sort through what’s happening here.

In the meantime, they’re also for me.

I was recently reading more about Christopher Anderson — the photographer who took those excellent uncomfortably-close White House staff portraits — and I liked this anecdote. He’d been documenting a boat full of Haitian migrants when it began to sink.

We were doomed and we knew it. We started saying goodbye to one another. Strangely, it was quite calm on the boat. There was not much to do except resign oneself to the inevitability of it all. Up to that point, I had not taken many pictures. Everyone on the boat knew I was a photographer, but it somehow had not felt right. It’s difficult to explain. But as the boat sank, David, the Haitian whom I had followed on this journey, said to me, ‘Chris, you’d better start making pictures. We only have an hour to live.’ And so, without much thought, I began making pictures.

We were saved at the last moment by a US coast guard cutter that happened upon us, but that’s another story. Much later on, back home safe, I reflected on this question: why make pictures that no one will ever see? The only explanation for me was that the act of photographing had more to do with the explaining of the world to myself than explaining something to someone else. The pictures were about communicating something about my experience, not about reporting literal information. This would be the single most transformative moment of my photographic life.

I had it backwards back in Pittsburgh.

I don’t know whether this newly-rediscovered passion for photography will ever successfully explain things to others, but right now it’s helping me explain the world to myself. For now — as the year comes to a close — that’s enough.