"Humanity-based propaganda."

Reflections on "extinction bursts," Christopher Anderson's Vanity Fair photoshoot, his Washington Post interview, and my own year photographing people

Alexandria Augustine, founder of the Human Liberation Coalition — one of the main groups on the ground protesting the Metropolitan Detention Center in Downtown Los Angeles — shared a video on Instagram yesterday that I found fascinating.

She talks about the concept of “extinction bursts,” a term from behavioral psychology. An “extinction burst” is the period where you stop reinforcing a bad behavior, and it gets worse before it goes away. The classic example is a parent’s attempt to stop a child from crying for attention; when they initially stop reacting to the cries, the child cries even harder before realizing it’s not going to work anymore.

Alexandria applied this to our current political moment. For a while there, we tried to stop rewarding political cruelty (cf. “woke-ism,” etc). Right now — in response, as a backlash — the cruelty is getting rapidly more intense.

In the video, she suggests ways that we can use techniques from behavioral therapy to alter the course of this political behavioral escalation. Her first technique is called “visual prompting,” which refers to communicating with images rather than words. Nonverbal children, for example, use something like the Picture Exchange Communication System, arranging images to communicate their thoughts.

“The visual prompting that we are seeing our government enact on the public is the propaganda, right?” she said. “... And so, our form of visually prompting this extinction burst would be our own humanity-based propaganda. They have their machine; we need ours, right? So, really focusing on the reality of, you know, farm workers, for example, who are really suffering. Our school systems. The reality of what it is like to have ICE and the military occupying your city.”

That phrase — “humanity-based propaganda” — really resonated with me.

I think that’s maybe what I’ve been trying to do all year.

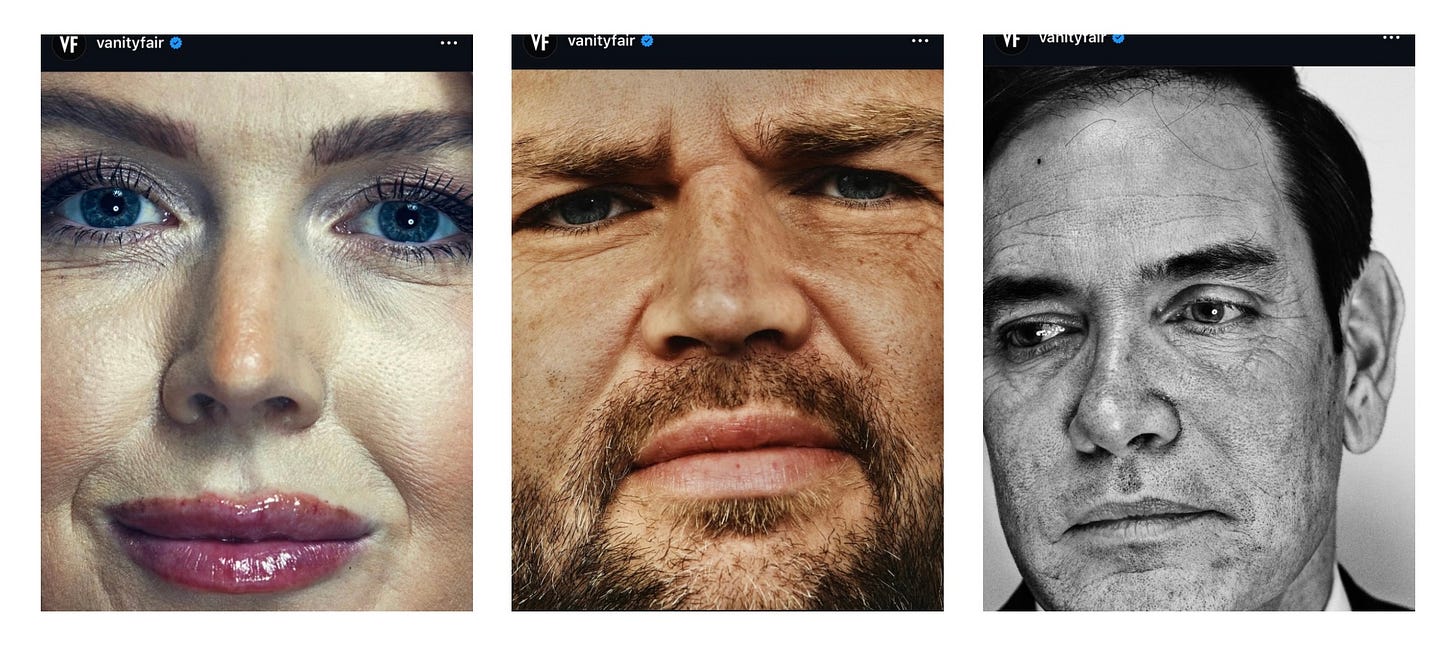

I moved past Christopher Anderson’s Vanity Fair photos too quickly yesterday.

I started Tuesday morning laughing that the White House staff would allow themselves to be photographed like that; I ended the day crying at the Planning Commission meeting in California City, listening to speaker after speaker describe horrifying human-rights abuses at the for-profit ICE facility operating illegally in town while local bureaucrats sat impassively.

Anderson’s images clearly reveal the performance of power, the desperate-to-be-liked vanity of these people who cause so much human suffering. People laughed at the visible lip-injection sites on Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt’s lips, I assumed, writing yesterday that it’s also important to recognize that evil — in the banal, Hannah Arendt sense — comes in the form of people who aren’t performing power, who are just small-town citizens caught up in the grip of something massive.

I said the iconography Anderson was working with was “obvious.”

I think I missed the bigger story. I’ll blame the fact that I — again — was busy looking into the eyes of the volunteer local government officials who seem likely to soon retroactively rubber-stamp the CoreCivic ICE facility. Yesterday, I flew across the country, only three hours of sleep away from — can’t emphasize this enough — seeing how desperately-normal the room was where the operation of a torture facility will soon be retroactively approved.

That bigger story is: the iconography was apparently not at all obvious, and apparently it got “backlash” on social media.

Photographer Barry Morgenstein, for example, wrote on Threads, “The photographer Christopher Anderson who took that very closeup, unflattering photo for Vanity Fair of Karoline Leavitt is a punk and unprofessional … A photographer’s job should be to capture the true person as themselves.. Even if I did not agree with my clients politics , I would never shoot an unflattering photo of them!”

He shared his own photo of Leavitt, calling her a “natural beauty.”

I’m so tired.

The Washington Post got ahold of Anderson and asked him to justify himself.

That’s crazy.

Framing their questions as “some people are reading this as an attack or being petty” and “what is your response to people who say that these images are unfair,” they needled him about why he chose to photograph the White House staff in that way.

His answers are great. “People seem to be shocked that I didn’t use Photoshop to retouch out blemishes and her injection marks. I find it shocking that someone would expect me to retouch out those things,” he said. He later added, “I’m surprised that a journalist would even need to ask me the question of ‘Why didn’t I retouch out the blemishes?’ Because if I had, that would be a lie.”

For David Farrier’s Webworm, I wrote a piece about the reaction to my own images on Reddit, where people seem unable to interpret context anymore, or to grant that a photographer might be making intentional choices. People love to tell me things I already know about the images I posted.

Yesterday, on the /r/LosAngeles subreddit, I shared a selection of photos and wrote a caption about California City, CoreCivic, the things we heard from detainees, and how I fixated on the “desperately-ordinary room” that such evil things were being discussed in.

I couldn’t help but reply to this one.

There were a fair few along these lines. Plenty of people accused me of sensationalizing things. One person wrote, “How do you retroactively grant permission to do something? It’s not possible. That wording was to make what’s happening sound worse than it is.”

…again, that’s precisely my point. Retroactively granting permission to torture people — something that’s so much worse than we let ourselves believe — is a bizarre justification that can come from these normal-looking people in this normal-looking room.

Since June, I’ve dealt with this online extensively. When I shared photos from the Dodgers World Series Parade and titled them “Absurdities of living in a police state,” people told me that because my photos didn’t show police brutality, “police state” was overblown. “There are plenty of actual examples of police violence you could’ve used instead,” someone said.

…but I took these pictures. If we agree that there are plenty of other examples that would prove “police state,” why can we not view these pictures in that context?

“Cops exist and need to be places,” someone told me.

Yes, but, I’m showing you images of someone dressed as Spider-Man, next to a bunch of cops surrounding a man in a wheelchair, next to a big blue guy trying to tie his blue shoe, next to a cop carrying a four-foot wooden sword in case she needs to beat someone with it. The word “absurdities” was doing as much work in that title as “police state,” but no one in the comments would let me have that. Any time I tried to explain that the meaning intentionally comes from absurdly-ordinary juxtapositions, they downvoted me until those comments were hidden.

I thought of these photos when I heard Alexandria say we need to show people “the reality of what it is like to have ICE and the military occupying your city.”

The “reality” is: it’s fuckin’ weird! Much of the city is going about normal life, but for some of us, everywhere we look are reminders of the awful truth we’re facing. I assumed we all understood that this is a “police state” because when I see six cops surround a guy in a wheelchair, I have in mind the fact that in the past few months I’ve taken photos not just of LAPD but of DHS, CBP, CHP, HSI, the USMC, the National Guard, and more.

Clearly, though, not everyone cares enough to consider that context as the base reality of every other facet of their lives. For me lately, it’s unavoidable. Everything happens in that context.

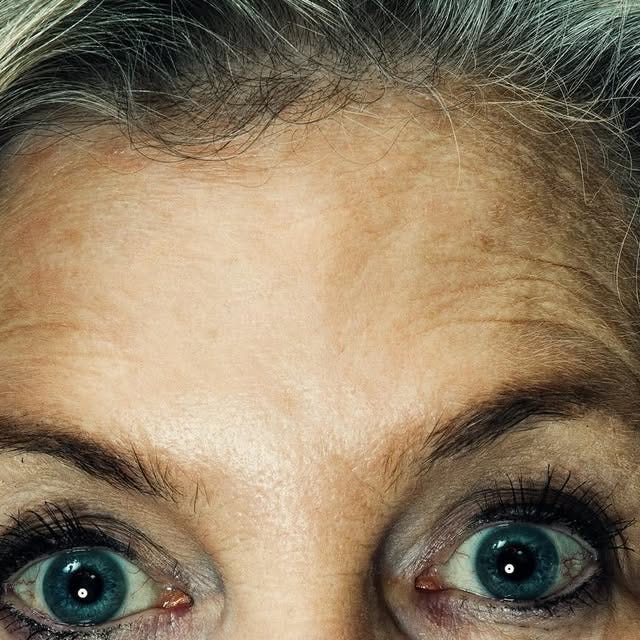

And then there’s the question of “close-ups.”

The Washington Post reporter who spoke with Christopher Anderson told him, “I thought it was interesting that Karoline Leavitt’s defense of Susie Wiles has been, ‘Everything was taken out of context.’ The extreme close-up divorces faces from context, as well. What’s your response to that?”

Anderson answered, “Does not seeing the beige wall behind them take them out of context? I’m not sure. Everything that’s in the frame is what I choose to keep in the frame. For me, in the case of close-ups, I am trying to eliminate certain information so that other information is easier to read.”

Yes, yes, yes!!

All year, people have questioned my decision to shoot primarily with a 75-300mm lens, which lets me get close-up portraits of people from a distance. People on Reddit have gone on at length about how my photos lack “context,” evidently considering each one in complete isolation rather than being willing to do the work of meaning-making.

I expect people to understand that the “context” of “a June closeup taken in Los Angeles of a masked man's blue eyes shining behind his visor” is “the news has been fixated on Los Angeles and its militarized response to ICE protests.” I expect people to understand that the “context” of a frustrated-looking bus driver is the 15 other photos in the slideshow of a protest in the street.

Last week, I shared a carousel of photos to Reddit showing the chaos that erupted at Los Angeles City Council when LAPD demanded they find an extra $4.4 million elsewhere in the city — by cutting someone else’s funding — because they’d hired more police officers than they were budgeted for. They were images like this:

I linked to the five-hour recording of the City Council meeting, shot from a camera in the corner of the room.

Someone commented on those photos, “Please use a wider lens 😭😭.” After I replied, they deleted it.

I love Christopher Anderson’s answer: “I am trying to eliminate certain information so that other information is easier to read.”

By eliminating whatever information the full view of the City Council dais would’ve given you — where everyone’s sitting in relation to each other, I guess? sure! — I am making it easier to read the emotion on City Controller Kenneth Mejia’s face as he watches the debate.

By eliminating the information a wider lens would’ve given you about how many people are in the room, I can zero in on the cop in the corner unable to control his laughter.

By eliminating the ornate decorations that surround the LA City Council… by cutting out the LA28 Olympics flag, the American flags, the studio-quality lighting, the cameras, the crowds of aides, the half-filled public gallery… I’m making it easier for you to read the way Councilmember Ysabel Jurado feels about the soap opera-quality backstabbing happening between her colleagues.

So, maybe that’s “humanity-based propaganda.”

We tend to think our problems stem from all these massive, impersonal systems — “government” vs. “immigrants” vs. “protesters,” etc. — and on some level, they do.

But I guess I’d say that I’ve learned this year that I want my photography to make people think about the fact that these collective nouns are made up of humans — people with emotions, backstories, reactions, and motivations that we sometimes show each other on our faces.

Is that “propaganda?” Maybe! People on Reddit love to tell me that I’m pushing a narrative, selectively choosing moments that fit a storyline I want to convey. …Yes, correct! That’s the job of an artist — to select certain elements that paint a picture, so to speak.

The picture I want to paint is one of a Los Angeles facing history… but I want to document the people who live in Los Angeles who are facing history.

So, bravo, Christopher Anderson. Bravo, Alexandria Augustine. I want to follow their example.

Because a photo showing an entire protest crowd and police line simply does not tell you the same thing that, for example, this photo does.